Blessed be everyone.

I found this last night while searching the web for something about having some 'alone time'. I really enjoyed reading it and I wanted to share it with you all this morning, especially since the particular 'Thought for the Day' post was about 'Solitude'.

I hope that you all will find it enlightening and inspiring as much as I did.

*************************************************************************************

Solitude: Seeking Wisdom in Extremes

by Bob Kull

Posted by: DailyOM

Years after losing his lower right leg in a motorcycle crash, Robert Kull traveled to a remote island in Patagonia's coastal wilderness with equipment and supplies to live alone for a year. He sought to explore the effects of deep solitude on the body and mind and to find the spiritual answers he'd been seeking all his life. With only a cat and his thoughts as companions, he wrestled with inner storms while the wild forces of nature raged around him. The physical challenges were immense, but the struggles of mind and spirit pushed him even further.

Solitude: Seeking Wisdom in Extremes is the diary of Kull’s tumultuous year. Chronicling a life distilled to its essence, Solitude is also a philosophical meditation on the tensions between nature and technology, isolation and society. With humor and brutal honesty, Kull explores the pain and longing we typically avoid in our frantically busy lives as well as the peace and wonder that arise once we strip away our distractions. He describes the enormous Patagonia wilderness with poetic attention, transporting the reader directly into both his inner and outer experiences.

Kull went into solitude fishing for enlightenment, seeking the Answer, but came back empty-handed. Wilderness, he found, is a place to clearly see the insanity of denying that the world is as it is. He discovered that life itself teaches us all we need to know — once we pause to really listen.

Excerpt:

But when I left the magic of the forest and returned to the chaos of the human world, I lost my way, and the clear inner light faded. I traveled to Mexico with my lover, and sat for long hours by the sea, but caught only brief glimpses of the joy and wonder I'd thought would always fill my life. I didn't know what I'd done wrong, but I felt I'd somehow failed an important spiritual test. I sank deeper and deeper into darkness, clinging to the dead memory of what had been a living flame. My lover tried to understand, but I couldn't explain what I was going through, and she finally left me.

Alone again, I drifted north to California, and lived for a while in a cave in Death Valley — sleeping long hours and attempting to interpret my dreams. During the day, I read the Bible and Carl Jung, trying to understand and accept what had happened to me in the wilderness, without getting sucked back into the fundamentalist Christian dogma I'd grown up with. The depression and the grief for what I'd lost eased only when I discovered Buddhist meditation practice and learned that peak spiritual experiences are inherently transient.

As my mind cleared, I began to remember something I'd thought about in the wilderness. When I was twenty, I'd left the United States to live in Canada rather than fight in the Vietnam War. It had been an ethical choice, but during the months in solitude I came to recognize that I'd avoided an important social responsibility: not to go to war but to contribute two years of my life to serve the community in a positive way.

A friend told me about an agency that sent volunteers to teach organic vegetable gardening in the Caribbean. I signed up to spend two years in the rural mountains of the Dominican Republic, beyond the reach of cars, electricity, and running water. A month after I arrived, the agency sent word that they had lost their funding and I should use my return ticket back to the States.

But I believed in the work and decided to stay. I built a small shack to live in, continued to cultivate the demonstration garden, practiced my Spanish, and traded vegetables for the staples I needed. I also did small carpentry jobs to earn the thirty dollars a month I learned to live on. After I'd been there for a year, Hurricane David swept through and wiped out the homes of many of the poorest people in the tiny village where I was living. I abandoned the garden and focused on bringing in relief supplies, doing first aid, and rebuilding houses.

Despite the political strife that sometimes caught me up, those years were magical. The deep connection I felt was as much with the people as with the land, and I was overwhelmed by how much I received from those I had gone to help. Even though we didn’t share much intellectually, our heart connection was, and still is, strong.

Then I fell in love — with an American woman who was on the island filming the reconstruction effort. She returned to the States but came back to share my one-room shack. As a gift to her, I poured a layer of concrete over the dirt floor and replaced the dim oil lamp with a brighter propane light. We lived together in the mountains for two years before moving to the sea.

On the coast, I found a job running the water sports department in a resort hotel, where I learned and taught windsurfing and scuba diving. The party atmosphere of the Caribbean was very different from our quiet life in the mountain village. We began to each go our own way until our relationship broke, and I was alone again...except for a steady stream of tourist women. During the next four years, the inner light almost flickered out as I leapt jubilantly into sex, alcohol, and scuba diving. Then one morning, while I was riding my motorcycle across the island to go diving with humpback whales, a drunken farmer crashed his pickup into me. I was flown to Montreal, where the doctors in the Royal Victoria Hospital tried unsuccessfully to reattach my right foot, which had been ripped off in the crash. When I emerged from the hospital a year later with a prosthetic leg, I'd lost my dive business and could barely walk. My life in the Caribbean was over.

The World of Intellect

It was hard to accept that my body was no longer what it had been, but rather than cling to what I'd lost, I focused on developing my mind instead. I decided to go back to school. I'd dropped out of the University of California at Berkeley when I was nineteen because I felt too restless to sit in a classroom. Rather than the nine-to-five office job I believed a university degree would lead to, I'd wanted a life of physical activity and adventure. Now at forty, I enrolled in McGill University to study biology and psychology. Studying science as a mature student was challenging and occasionally amusing. Sometimes, when I walked into a lecture hall on the first day of class, the other students would stop talking and sit up to attention...until I scrunched down into one of the desks among them. "Huh? He's not the professor? What's this old fart doing here?" It was often a lonely life.

I immersed myself in the intellectual world like a dry sponge soaking up a flood of new information. I'd always read on my own, but now I was studying in a directed and systematic way. I loved it at first, but slowly the academic approach began to pall, and by the time I graduated — with a fellowship to pursue a master's degree in biology — something vital was missing from my life. I felt as though I'd become a hollow shell filled with abstract facts and theories that seemed to have little connection to my heart or to my own actual experience. Once again I heard solitude calling and spent two months canoeing alone in northern Quebec. During that summer, the world came alive again. The sense of existing in a living universe was what had been missing in the university.

I decided against graduate school, worked for a year as a carpenter to earn money, and left for what I thought would be three months in Mexico. A year and a half later, after lingering in San Cristóbal de las Casas, Mexico, and Argentinean Tierra del Fuego, I found myself sailing up the remote wild coast of southern Chile. It was astonishingly beautiful, and during the three-day ferry ride, I began to imagine an exciting project that braided together two apparently disconnected threads of my life: I would use the money from the academic fellowship I'd been awarded to carry out a biological study, while living alone for a year in that pristine coastal wilderness.

I made my way back to Canada and enrolled in the master's degree program at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, but the deeper I settled into graduate studies, the more I realized that biology was not my main interest. What I truly wanted to explore was the effect of deep wilderness solitude on a human being — in this case, on me. I would be both researcher and subject. I also wanted to examine my relationship with the nonhuman world and to learn how the direct experience of profound belonging in the universe might lead to changes in human behavior that would be less damaging to the Earth. I expected there to be resistance among conservative professors to this unorthodox approach, but I would risk it. I transferred to the Interdisciplinary Studies PhD program.

One of the most important, but often trivialized, tasks facing a new graduate student is selecting a research supervisor and supervisory committee. This is the group that will most directly support or hinder the PhD process. Especially when wishing to carry out nonconventional research, choosing individuals who are open-minded, ready for adventure, and with whom you can openly communicate is vital. I was very careful and selected such people. They were excited about my proposal to study myself as I lived for a year alone in the wilderness. But there were two strong caveats: they offered no additional funding, and they did not guarantee that I would actually be awarded a PhD for the adventure. I willingly accepted those conditions.

My relationship with the rest of the university was sometimes less positive. Mostly, I pursued my academic study on my own. I had friends among my peers, but no close associates. The faculty frequently treated me with amused tolerance rather than respect or disapproval. One professor told me I was too old for such a radical project, that such things were for younger people. I suspected his comment might apply to my graduate work in general. A fellow graduate student, who was also doing nontraditional research, said she was very glad I was in the department because my project made everyone else's seem fairly conventional.

I learned an important lesson at the university. Walls of resistance often turn into doorways if you lean steadily against them for a while. Once I was asked to give advice to a group of new graduate students, and I suggested that they take as long as possible to earn their degree. At first their supervisory committee would find many reasons why their dissertation was not acceptable; eventually the committee would just want to get rid of them and would support damn near anything. Of course the quality of the work must be excellent when you step outside the usual framework.

Welcome to my online Book of Shadows.

A good place to come and learn from and share with like-minded Pagans and Wiccans of all Traditions.

glitter-graphics.com

glitter-graphics.com

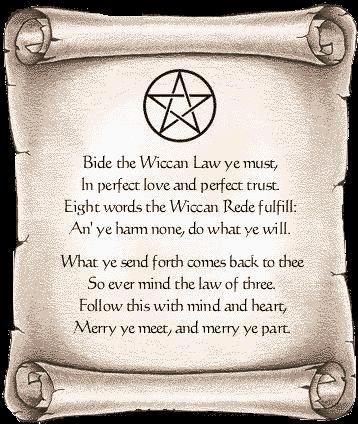

Wiccan Rede

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Live Traffic Feed

Being

Breath

Courage

Fight for Freedom

Earth Air Fire Water

Talisman

Spellwork

Moon Goddess

Moon Phases

CURRENT MOON

No comments:

Post a Comment