Blessed be everyone.

I do Tai Chi exercises daily before starting my day, and before going to sleep because I find it so relaxing and peaceful. I have probably 5 Tai Chi DVDs in my collection that I use daily.

I was trying to find a place to order Tai Chi DVDs online and happened across this article, which I found to be not only interesting, but very informative as well, and, as always, I had to 'copy & paste' it to share with you all.

I hope you enjoy it.

*************************************************************************************

Tai Chi: Health for Life

From "Tai Chi: Health for Life" by Bruce Kumar Frantzis

Posted by: DailyOM

Put simply, chi is that which gives life. In terms of the body, chi is that which differentiates a corpse from a live human being. To use a Biblical reference, it is that which God breathed into the dust to produce Adam. It is the life-energy people try desperately to hold onto when they think they are dying. A strong life force makes a human being totally alive, alert, and present; a weak life force results in sluggishness and fatigue.

The concept of “life force” is found in most of the ancient cultures of the world. It underlies Chinese, Japanese, and Korean culture, where the world is perceived not purely in terms of physical matter, but also in terms of invisible energy. In India it is called prana; in China chi; and in Japan ki. In some Native American tribes it is called the Great Spirit. For all these cultures, and others as well, the idea of the life force is central to their forms of medicine and healing. For example, acupuncture is based on balancing and enhancing chi to bring the body into a state of health.

Energy can be increased in a human being. Consequently, the development of chi can make an ill person robust or a weak person vibrant; it can enhance mental capacity too. The concept of chi also extends beyond the physical body, to the subtle energies that activate all human functions, including emotions and thought. Unbalanced chi causes your emotions to become agitated and distressed. Balanced chi causes your emotions to become smooth and more satisfying. From the perspective of thought, when your mental chi becomes more refined it enhances your creativity at all levels—art, business, relationships, child rearing, etc. Spiritual chi makes it more possible for us to personally enter into higher states of consciousness, which lie at the heart of religious experience.

Tai chi, and other forms of Taoist martial and healing arts, help you develop subtle chi energy.

Tai chi’s parent is Taoism. Over 5,000 years old, in its oral tradition, Taoism is known for its emphasis on nature, harmony, balance, chi energy, magic, and mysticism. Although it has fewer adherents than Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, or Buddhism, Taoism is a major world religion that continues to nourish the deepest needs of the human intellect, heart, and soul.

However, not all religions specifically heal and maintain the body’s physical health or balance the energies of the body so that it does not become stressed. The Taoist tradition does—not by its poetic, inspirational texts, but through its time-tested practical applications, such as tai chi chuan, designed to implement Taoism’s basic tenets.

Taoism is unique in that it is probably the only major religion in the world whose practitioners as a rule have not sought great secular power. In the past, Taoists took on such power only out of necessity to correct specific abuses. After these excesses had been corrected, they were always ready to relinquish the power and fade away, or “leave no footprints” as they put it.

Taoism has many sides to it: practical, religious, mythological, scientific, magical, and mystical. Taoist philosophy considers the outer power structure of civilization, including its politics, military power, and economics, to be fleeting and of no assistance to people in their spiritual search to find the essence of their nature. The structures of outer power simply allow us to go about the business of practical daily living with a minimum of chaos, with adequate food, shelter, and clothing. Taoists were also known as the scientists of ancient China. At that time, they were responsible for most of the nation’s major scientific breakthroughs.

Being useful is a central value of Taoist philosophy—how something is useful, why it is useful, and for what. The context could be anything you could possibly conceive of, regardless of perceived value, including health, wealth, social interaction, morality and ethics, spirituality, or a tai chi movement. Practicality is the mantra. Instead of asking if you ought to be conventionally moral or if it doesn’t matter, Taoists would ask “is it useful to be moral?” The answer would be yes. Rather than focusing on your narrow self-interest or the wrath of God, Taoists genuinely consider what the natural consequences are to yourself, human relations, the entire society, and spirituality if you are not moral.

The outer branch of Taoism is called tao jiao. Practitioners pay homage to one or many gods, visit temples where they pray, seek protection from spirits, bury their family, seek indulgences, consult mediums (especially about their ancestors), have their fortunes told, or receive other services expected from various non-Abrahamic religions worldwide. Tai chi comes from the inner or esoteric branch of Taoism, called tao jia. Followers of esoteric Taoism do not believe in or worship any God or gods but instead focus purely on the internal spiritual unfolding of the individual. They put the emphasis on individuals personally finding within themselves the Tao, the Body of Light, or God within. This inner esoteric tradition sees Creation’s source and all its manifestations as contained within each human being. Part of the Taoists’ spiritual investigation seeks to understand the ways in which the energies that compose the universe are revealed. They also believe that the mystic consciousness that underlies the universe can only be found within, by exploring the deepest esoteric and mystical possibilities of the human condition. In this sense, Taoism, by its very nature, has always been, and still is, primarily a living, esoteric mystic religion. Taoism’s Literary Traditions: the I Ching,

Lao Tse and Chuang Tse

Most people know Taoism through its ancient literary works—The I Ching, commonly used as a divination, advice, and mathematical tool, and the elegantly written philosophical works of Lao Tse and Chuang Tse2. These inspirational works also lay the practical foundations for tai chi chuan and other Taoist energy arts.

The I Ching

The I Ching, with an oral tradition going back 5,000 years, is considered to be the Bible of Taoism. It is concerned with the underlying nature and functions of all change. It also happens to be the mathematical basis of computer code, and a divination tool that untold millions of people have used to decide which way to go in uncharted waters.

Using obscure coded language, many passages in the I Ching are the direct source for an immense amount of technical details within tai chi. These include all its yin and yang principles, techniques from the simple to the complex, and strategies for all kinds of flow patterns within it. Equally, from the I Ching’s viewpoint, tai chi is a way to embody and actualize the I Ching within the human body, mind, and spirit.

Alternately spelled I Jing or Yi Jing, Laozi or Lao Tsu, Juang Zi or Chuang Tsu. I Ching is pronounced “ee jing” as in “jingle.” The tse (or zi) of Lao Tse and Chuang Tse is a sound not found in English or most Western languages.

Tai chi’s technical details come from the I Ching and the classics of traditional Chinese medicine, such as The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine. Tai chi’s underlying philosophical context, however, derives from the texts and oral traditions of the ancient Chinese sages Lao Tse and Chuang Tse. Both followed the same mystical principles of the Tao, but in very different ways. Lao Tse was the lofty, deep, and dignified sage, while Chuang Tse was the earthy, irreverent, enlightened hippie. Lao Tse had a very dignified demeanor; Chuang Tse was more like a character out of an unconventional hip television comedy with a wild and sharp theater-of-the-absurd personality and perspective. Both Lao Tse and Chuang Tse lived in a time and place where everything that comprises what we call life, be it sublime or from the gutter, was seen in the context of the sacred. Both were non-moralistic and mystical.

Through the lens of what is useful, both constantly looked for emptiness and the Tao in the actions of life, rather than purely focusing on the results of specific actions.

Lao Tse wrote the Tao Te Ching, called in English “The Way and its Power (or Virtue).”

After the Bible, it is the second most translated book in the world. Although Lao Tse passed down the broad tenets of Taoism, the oral tradition from which these principles came existed for thousands of years before his birth. His book was written 2,500 years ago during China’s Warring States period. Like the world today, at that time China was in a very confusing state, well described by the famous Chinese curse, “May you live in interesting times.” Lao Tse’s ideas give tai chi its incredible emphasis on the power of yin, softness, and returning to the natural easy power of a child. His timeless words are a profound vision of life on many levels. He advocated returning to a natural way of life. He saw incessant competition as damaging to society, the environment, harmonious relations, and spirituality.

He looked at human conflict and war and how leaders could smooth, mitigate, or

circumvent potential damage. He offered gentle antidotes to pervasive anxiety and the effects of stress on every level. He investigated the roots and proposed solutions for the lack of personal morality, and insight into loss of faith in corrupt and ineffective political, religious, and economic institutions. He expounded on the qualities of a teacher or leader and the path of patience and integrity. He felt that the more human beings want, the less they spiritually have.

Lao Tse’s philosophy had a strong emphasis on personal health, longevity, and spirituality. He saw never-ending striving and not following the natural ebbs and flows of life as corrosive to health and peace of mind—especially as we age. He saw tranquility, naturalness, moderation, and keeping the innate soft quality of an infant as the foundations of health and healing. Lao Tse advocated allowing things to happen, rather than making or forcing them to occur. He likened the Tao to the empty nature of water that can be everywhere, and yet assume virtually any shape or quality while maintaining its essential nature.

Chuang Tse wrote The Book of Chuang Tse, the third seminal work on Taoism, and

another of the major underpinnings of tai chi. While both Lao Tse and Chuang Tse

emphasized the power of yin—softness and returning to the natural state of a child— Chuang Tse also emphasized developing the quality of spontaneity until it infuses all actions and becomes natural, even under the most challenging conditions. Spontaneity and naturalness are the qualities that tai chi practitioners attempt to achieve in the tai chi form and in their daily lives.

Chuang Tse’s writing encompasses the most sublime mystical viewpoints, contained within a very down-to-earth style. His writing is full of anecdotes and tales, and a wicked sense of humor that strongly influenced medieval Zen Buddhists in Japan and Western hippies of the twentieth century.

Chuang Tse took the process of spirituality and the Tao very seriously, without taking the spiritual process, its followers, or himself seriously at all. He irreverently poked fun at everyone’s beliefs and judgments, spoken and unsaid, spiritual and secular. Why? To help people avoid the consequences of becoming self-absorbed and rigid. Chuang Tse saw the overly serious or inflexible approach of his Confucian contemporaries as creating all-pervasive judgments that could suffocate the human spirit and sidetrack deeper spiritual possibilities, and would not reflect the true needs of life’s spiritual or pragmatic situations. As an antidote, Chuang Tse emphasized the higher calling of spontaneity and pure awareness over rigid conduct and belief, with its attendant investment in “political correctness” and a tendency to repress those who disagreed. However, his spontaneity was not based on license—do what you feel like no matter who gets hurt, and damn the

consequences. Rather it was based on the spontaneity of a child, but, unlike childishness, it was rooted in deep awareness.

Taoist Energy Arts

Taoist energy arts are practical chi applications from the Taoist esoteric meditation tradition for living a better life.

The Taoists recognized that most people are not truly interested in anything beyond

surface spirituality. However, many people care about things they want and perceive as useful. The Taoists reasoned that if you gave ordinary people practical chi energy techniques that would get their needs and desires met, they would use them. You could call these chi practices “energy arts” for living well in the world. They are termed arts because, as in all arts to varying degrees, your chi is being directed outward to produce specific effects, whereas meditation is primarily an inward-directed experience. These arts create balance within you and allow you the opportunity to gain health, peace of mind, wealth, success, and personal power. These are useful, worldly qualities that most people want. Taoists also compassionately hoped if you practiced energy arts long enough a “wonderful accident” or event might occur where you would gain a direct spiritual perception of the potential depths of your heart and the Tao. Even if this experience was only fleeting, it still might awaken in you a real passion for spiritual realization and balanced compassionate human behavior—not because you were told to behave in this way, or because a motivational speaker charged you up, but as a result of a deeper and more genuine spiritual need that could be realistically sustained long term—meditation through the back door, so to speak. The wise Taoists said, “Give them what they want, so they will ultimately want what they truly need, realization of consciousness,” whether its name be Tao or God.

After the wonderful event happens, and you delve into spirituality and meditation, the outer structure of the energy arts continues as you learn to experience ever more profound internal levels. Eventually, step-by-step, the arts lead you to what is called internal alchemy.

Here the Taoist energy arts reveal their fullest possibilities.

Taoists also reasoned that even if the “wonderful accident” never occurred, at least

those who engaged in the energy arts would become healthier and more balanced

individuals, and live better lives. Benefiting humanity is a cornerstone of Taoism, and Taoists believe that balanced people are better able to provide long-lasting solutions to the world’s real problems. They considered the time and effort spent on spreading Taoist energy arts to be well used whether or not they furthered spiritual realization.

The Taoist meditation tradition helps people attain spiritual realization by working with and balancing chi energy, both personal and universal: hence the term energy or chi arts. Taoist meditation has various stages and progressive energetic practices including the higher transformational practice known as “internal alchemy.” These practices lead you to fully understand how within you is a tiny seed that is identical to the underlying essence of the whole universe. They allow you to realize in your entire being, rather than only intellectually, how the universe exists inside you and you inside the whole universe, and how to free your spirit from the limitations of the human body. It is said that through meditation you can achieve spiritual immortality in which you awaken and become fully conscious of your own soul or being.

Most people, however, aren’t quite ready for this. They are not willing to commit to a task equivalent to finding the Holy Grail. When I asked my teacher Liu Hung Chieh why he didn’t teach Taoist alchemy more openly, he said, “Not many people want to learn.” Taoist energy arts fall into three camps:

1. Arts that enable you to access and personally experience chi within yourself.

These include:

• Chi gung.

• Internal martial arts—such as tai chi, ba gua, hsing-i, and liuhe bafa.

• Taoist meditation.

2. Arts that enable you to feel chi within yourself and to perceive and work

with the chi of other people, for example therapeutic energy massage, called chi gung tui na in Chinese.

3. Arts that do not require you to have ever directly experienced chi yourself,

but which are more powerful and effective if you do. These were originally

based on people’s capacity to feel chi, but most practitioners today have little

experience of it. Included within these categories are:

• Chinese medicine, including herbs, acupuncture, bone setting, and ordinary

therapeutic massage (tui na).

• Fine arts such as painting and calligraphy.

• Feng shui (literally “wind-water”), known in the West as geomancy. This is

concerned with how the positions of the external energies of the earth, sun,

sky, landscape, physical materials, color, and time can affect people, animals,

and possible events. This enables you to mitigate problems, promote harmony, or create advantageous conditions in either natural or man-made structures.

• Politics, war, science, astrology, and metaphysics.

The question naturally arises, why so many Taoist energy arts? The answer is that a lot happens in this world and different people have different natural aptitudes, interests, likes, and dislikes which can be used to make the work of learning about chi a pleasure rather than a chore. You might want to heal but not fight, or vice versa. You might easily become drawn to and fully engaged in martial arts and painting but not feng shui or astrology, or vice versa. The more you become involved with your own natural interests, the more easily you can delve into and understand how your own energies work personally and universally.

Chi Gung Chi gung is alternately spelled qi gong (pinyin), ch’i kung (Wade-Giles), or chi gung (Yale), depending on the translation system that is used. Chi gung literally means “energy work.” It is the practice of learning to control the movement of the life force internally, by using the mind to direct energy in the body. Physical movements may be used but are not necessary, with standing, sitting, lying, and sexual techniques commonly utilized. Chi gung practices include many of the ancient Chinese techniques for increasing life energy. Increased life energy manifests itself in a variety of ways, from improved physical health to greater mental clarity and spiritual awakening.

Regular practice of these exercises will lead to a body and mind that are functionally younger, so that one’s “golden years” are truly golden rather than rusty. Standing chi gung with the weight

Guy Hearn

For more than 3,000 years, chi gung’s life-giving on the back leg. medical and meditative techniques have benefited hundreds of millions of people by helping them achieve physical health, emotional well-being, longevity, and peace of mind. This “new discovery” is now being reawakened to help people in the West, just as it has for millennia in China. In our new computer age, with ever-increasing mental workloads and time pressures, we may need soft, revitalizing chi gung exercises even more than the ancients.

The Different Branches of Chi Gung

There are five major branches of chi gung in China: Taoist, Buddhist, Martial Arts, Medical, and Confucian. Each branch has various sub-schools, commonly called systems in English, and each system has sub-categories called styles, each with specific names and histories and related movement forms.

Separating out the different schools of chi gung is not so easy. In order to fully understand the functions, underlying rationales, strong and weak points, and benefits or potential downsides of most chi gung systems you are likely to encounter, it is helpful to understand clearly both the essential philosophies and methodologies of the Buddhist and Taoist systems. Often the classification and name of a chi gung method—Taoist, Buddhist, or Family system, etc.—doesn’t actually describe what it does. The name in the advertisement does not guarantee its authenticity, or indicate what you will go through if you learn and practice. The words and the real goods may be different. Mixing bits and pieces of different systems often creates specific chi gung styles. The pieces of a “new style” may successfully fit together and integrate in a coherent and complete manner. Or they may fit together in a mediocre hodgepodge, which is confused or ineffective. Many “family chi gung systems” that claim to go back hundreds of years may in fact have been recently created. The story, myth, or history any given chi gung system says about itself may or may not be true. This situation is common both in China and the West.

Taoist Chi Gung

Over 3,000 years ago, meditation adepts discovered and systemized Taoist chi gung, the progenitor of all the different forms of chi gung and tai chi. They did so by going deep inside themselves. Using their powers of inner awareness, they became able to directly perceive the body’s energy flows—energy channels, points, and interrelationships between the internal energy systems of the human body and its physical tissues, including internal organs, glands, sphincters, bodily fluids, soft tissues, bones, and bone marrow. These same adepts created traditional Chinese medicine, including acupuncture, healing with herbs, bone setting, and therapeutic “chi” bodywork.

Taoist chi gung is based on softness and is valued for its ability to regenerate the body, allowing you to feel and function as a young person when moving into middle age and beyond. It is composed of 16 irreducible components, called nei gung by the Chinese, which means inner or internal power work (see pp. 235–240). Its methods help open the mind and calm the heart by emphasizing inner stillness, letting go, softness, and relaxation.

Although its work can be subtly intense, the trademarks of Taoist chi gung in its purest form are:

• Complete relaxation of the body’s muscles, tendons, and ligaments.

• Smooth, even, silent breathing and never holding the breath.

• Movements that are soft, smooth, fluid, and circular with a sense of ease

and comfort.

• Total utilization of effort, but only to the point of not creating internal strain.

• Physical stretches that are accomplished by release, relaxation, and letting go of tension in the nerves and mind, instead of relying on force or willpower to push the muscles.

The Differences Between Tai Chi and Chi Gung

Tai chi and chi gung have both similarities and differences, and are often confused with each other. There is no simple way to describe the difference between the two. Appendix 1 sets out the explanations most commonly given and describes why these explanations only give a partial picture.

Conclusion

Hidden within tai chi’s slow-motion movements are the gems of the accumulated wisdom of China. Its great depth is immensely useful today. It is a living, cultural legacy of the ancient world that can help you improve health, reduce stress, and make your later years richly satisfying and truly golden.

Tai chi is more than a martial art and more than most forms of exercise. It has a deep

philosophical and spiritual perspective. Its gentle, slow-motion movements and sophisticated methods of systematically moving life force or chi within the body teach you to relax and open up to your full human potential on all levels—physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual.

From Tai Chi: Health for Life by Bruce Kumar Frantzis, published by North Atlantic Books, copyright © 2006 by Bruce Kumar Frantzis. Reprinted by permission of publisher.

Welcome to my online Book of Shadows.

A good place to come and learn from and share with like-minded Pagans and Wiccans of all Traditions.

glitter-graphics.com

glitter-graphics.com

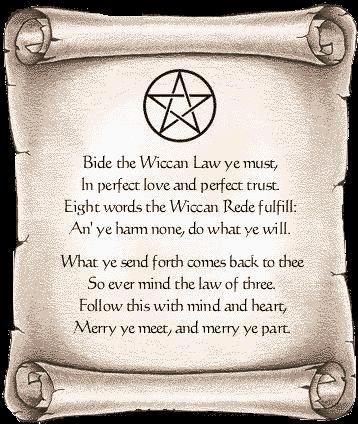

Wiccan Rede

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Live Traffic Feed

Being

Breath

Courage

Fight for Freedom

Earth Air Fire Water

Talisman

Spellwork

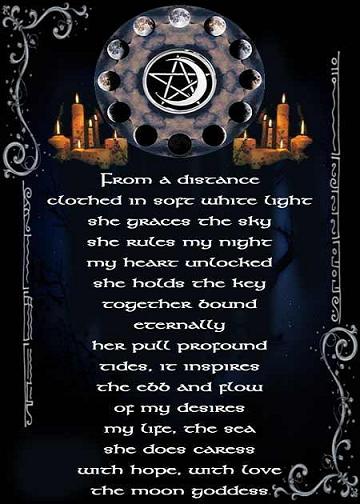

Moon Goddess

Moon Phases

CURRENT MOON

2 comments:

Have you checked out Gaiam.com? They have all sorts of groovy things to include indoor composters, organic clothing, and awesome yoga DVDs.

Hello,

I do a lot yoga but I have find tai chi to be very relaxing. It is a way for me to use my body and spirit together at the same time. I think its great that you practice tai chi on a daily basis. I believe doing things such as this can help you handle stress in natural and healthy way. Blessings to you...

Post a Comment